Building a Visual Novel Engine Part 2 - Route Engine

This series will explain the whole architecture and design of RouteVN Creator. By the end of the series, you should have a good understanding of how RouteVN Creator works, and essentially how to build a Visual Novel engine from scratch.

This is part 2 of a 3 part series:

- Part 1 - Route Graphics: a declarative graphics and sound library

- Part 2 - Route Engine: a Visual Novel engine built on Route Graphics

- Part 3 - RouteVN Creator: a Desktop application to create Visual Novels without any coding

Route Engine

Route Engine is all about the Visual Novel domain. It takes all the capabilities of Route Graphics and turns it into a full-fledged Visual Novel engine.

There were a few goals, or rather constraints, that shaped the outcome of this library:

- All graphics and audio will be handled by Route Graphics

- All content lives in a single JSON object

- The engine runtime executes that content into a fully playable Visual Novel

In this article, we'll:

- Cover the background and challenges

- Explain the JSON structure for Visual Novel content

- Dive into the runtime implementation

- Share our conclusions

Background

Visual Novels engines have been built for decades, there have been hundreds built before. Yet only a few become big and mature enough to have a significant userbase. Most development stall within 1 or 2 years. This got me thinking a lot.

Building a Visual Novel engine is deceptively simple, but it is hard in reality.

On the surface, it seems like just putting images and text on screen at specific coordinates. That's easy, and it's something that can be built quickly. This is why there are more than a dozen new VN engines every year. You need to create wrappers around a graphics layer and add Visual Novel-specific logic.

On the other hand, building a Visual Novel engine is basically building an entire game engine. That's a huge engineering project. You have to manage game state, record progression for save/load/rollback, interactive UI, and asset loading, manage variables. A Visual Novel's graphics are simpler than other games, but you still have to implement everything. You can also think of it as a mini operating system.

If you're building a custom runtime for just one Visual Novel, it's relatively straightforward. You can hardcode everything. A Visual Novel engine, however, has two sets of users: the end consumer who reads the Visual Novel, and the artists and developers who use the engine to create content. The second group is much harder. You can't control what they want to make, and many issues are about usability rather than technical capability.

When you have to do both, handle complexity and serve creators, it becomes a non-trivial engineering project. One that takes many iterations and intentional design and planning.

We try optimize the engine for three things:

- Easy to use

- Able to scale to complex features

- Reliable performance and stability

An engine that grows in features but gets pulled down by bugs is something I wanted to prevent from the original design.

Route Engine has gone through many iterations and rewrites. Probably four or five. I've lost count.

Content vs. Runtime

The content is what the user creates. It's a JSON object. We like to write it in YAML when doing it by hand, but it is the same thing.

The runtime is the engine code. It's JavaScript, and the user cannot change it. This is where we need to implement all the functionality that is being exposed to the JSON object.

This is a fundamental design decision that shapes the engine. Users do not write actual Python or JavaScript code. We also don't expect users to write the JSON by hand. It's designed to be generated by another program.

The reason for this is our primary use case: Route Engine has been built to be used by RouteVN Creator. Our objective is to hide complexity and technicalities, exposing a simple, non-technical UI for users.

Having said that, it's very possible to build a scripting language on top of Route Engine. The engine implements all the features. A higher-level scripting language could wrap it to make it easier to use.

JSON Structure

Can an Entire Visual Novel Be Just a JSON object?

Possible? Yes, for sure. The problem is more about making it practical.

By practical, I mean mostly:

- Easy to use

- Achievable with limited time and resources

We're not talking about just graphics and UI like Route Graphics. We're talking about a JSON structure that represents everything including:

- Splash screens

- Menu pages with buttons

- Button click handling

- Fully customizable UI

- Dialogs and confirm boxes

- Auto mode, skip mode

- NVL mode, history mode

- Implementing variables and conditionals

- Scene transitions and animations

- Everything else you see in Visual Novels

What's not included:

- Mini games

- Customizations beyond basic Visual Novel features

All of this, without writing a single line of code. Is it practical?

We've been trying to do this for almost 2 years. The answer is mostly yes, but it's by no means easy, and we're far from done.

The key is that this isn't implemented in the JSON data structure itself. All these capabilities are implemented in JavaScript and exposed through the JSON interface.

Next, we'll go through this JSON structure and show how we represent a full Visual Novel with a single file.

Resources

We predefine all resources upfront. All Visual Novel assets are defined there.

Images can be used for backgrounds, CGs, and UI. These are the building blocks of the Visual Novel. We define everything with its respective properties, each with an ID for identification.

resources:

layouts:

base1:

elements:

- id: clickArea

type: rect

fill: "#000000"

width: 1920

height: 1080

click:

actionPayload:

actions:

nextLine: {}

storyScreenLayout:

elements:

- id: dialogue-container

type: container

x: 50

y: 300

children:

- id: dialogue-character-name

type: text

content: "${dialogue.character.name}"

textStyle:

fontSize: 24

fill: "white"

- id: dialogue-text

type: text

x: 20

y: 100

content: "${dialogue.content[0].text}"

textStyle:

fontSize: 24

fill: "white"

images:

bg-classroom:

fileId: classroom-bg

width: 1920

height: 1080

characters:

makkuro:

name: Yuki

tweens:

fadeIn:

name: "Fade In"

properties:

alpha:

initialValue: 0

keyframes:

- duration: 700

value: 1

easing: linear

Resources are pretty straightforward. But there are few things to note:

- We're careful about resource types we support. Layouts use the direct Route Graphics interface, so they're the most versatile

- We don't want to add too many types to prevent bloat. Keeping it simple is intentional, we only add a resource type when it is really necessary.

Story Hierarchy

This is a carefully designed data structure after many iterations to solve the branching and sequential content nature of Visual Novels.

We split the structure of a Visual Novel into:

- Scene: More like folders. They don't have much logic, but are useful for grouping sections

- Section: A chunk of content. A section has multiple lines. We can jump from section to section

- Line: A unit of content. Typically, one mouse click advances to the next line. A line is made up of multiple actions.

- Action: The smallest unit of change. It does one thing such as update background image or move character. All visible changes on the screen happen because of some action.

A section is composed of multiple lines. Jumps between sections can be fully invisible to the user (feeling continuous) or have significant transitions to feel like full scene changes.

During choices, when we need branching, we jump to another section.

Actions represent change. When we add a background, it stays there until an action removes or changes it.

Below is an example of such structure:

story:

initialSceneId: scene1

scenes:

scene1:

name: "Opening Scene"

initialSectionId: section1

sections:

section1:

name: "Section 1"

lines:

- id: line1

actions:

base:

resourceId: base1

background:

resourceId: bg-classroom

dialogue:

mode: adv

gui:

resourceId: storyScreenLayout

content:

- text: "The morning sun filters through the classroom window."

characterId: makkuro

- id: line2

actions:

dialogue:

content:

- text: "I take my seat and look around."

characterId: makkuro

- id: line3

actions:

sectionTransition:

sectionId: section2

section2:

name: "Section 2"

lines:

- id: line1

actions:

dialogue:

mode: adv

gui:

resourceId: storyScreenLayout

content:

- text: "We're now in a new section."

characterId: makkuro

Note how all resource identifiers are references with the ID, this removed duplication and forces consistency.

In this particular scene, the Visual Novel starts with a background and a dialogue box with text content. When the user clicks, it will show the next line with the updated text at line2.

When the user clicks again, the sectionTransition action is triggered, and will move to section2's 1st line.

This data structure represents well the Visual Novel mechanics:

- Within a section, content flows sequentially, you click and expect to move to the next line

- Between section to section, content flows in a branching fashion, you can jump to any section.

Rendering Dynamic Data

The above structure works well for static data, but actual Visual Novels are more dynamic.

By dynamic I mean that the UI may change depending on some conditions, such as a button should be shown only when a certain flag is active.

Another common example of dynamic data is the save/load screen. On this screen you can click at one of the save slots and it's content will update.

Our solution of enabling dynamic content is via a library called Jempl which is like a templating engine but for JSON.

Below are some examples:

Variables: Show current value

The value of this text comes from a dynamic variable

elements:

- type: text

content: "${variables.textSpeed}"

Conditionals: Show skip indicator only when skip mode is active

This skip indicator will be shown only when variables.skipMode == true

elements:

- id: skip-indicator

type: text

content: "SKIP >>"

$when: "variables.skipMode == true"

When calling the toggleSkipMode action, it updates the variable and the element appears/disappears.

Loops: Show save slots on the screen

This enables us to show repetitive content on the screen without hardcoding each one.

elements:

- $for item in saveDataArray:

- id: save-slot-${item.id}

type: container

children:

- id: slot-text-${item.id}

type: text

content: ${item.id}

The above covers the primitives to render dynamic content. These simple primitives can cover many more complicated cases.

The power comes from the fact that we were able to do this while keeping a JSON only structure and without needing the user to switch to a different language.

Interactive Elements with Actions

Interactive elements are the ones that you can hover, click, double click, scroll etc...

This is possible with a close integration between Route Graphics and Route Engine

- in the JSON, we specify an

actionPayloadon specific properties likeclick - Route Graphics emits the event with the payload

- Route Engine receives the event and handles it

Below is an example of a text button click:

elements:

- id: counter-display

type: text

content: "Count: ${variables.clickCount}"

x: 100

y: 100

- id: increment-button

type: text

content: "+"

x: 100

y: 150

click:

actionPayload:

actions:

updateVariable:

id: uv1

operations:

- variableId: clickCount

op: increment

When the button is clicked, the clickCount variable increments and the display updates to show the new value.

Challenges

Above, we've demonstrated how resources, story hierarchy (scenes, sections, lines, actions), and integration with Jempl and Route Graphics can create dynamic and interactive experiences.

But it's a big challenge. We're very constrained by the JSON structure, and we need to be careful about the functionalities we introduce. We try to balance:

- Making it too specific and hardcoded (not flexible, can't meet all use cases)

- Making it too general (hard to use, users create repetitive work, different users build their own abstractions)

Finding a good balance that correctly represents the Visual Novel domain takes many iterative steps. We are very careful about any new functionality in this JSON.

Any decision that we make on the structure of this JSON is carefully considered as it will have to be maintained for a long time, potentially forever.

Backward compatibility is another consideration. Any breaking change would require users to mostly start over their Visual Novel or migrate projects. We're willing to do this only when we find structural, worthy improvements that justify the breaking change.

That is all for the introduction of the JSON. Next, we will talk more about how this JSON's functionality is actually implemented in the JavaScript runtime.

Runtime

So far we've talked about the content. The JSON file that defines your Visual Novel. But who actually runs that content? That's the runtime.

Think of it like this:

- The JSON is like a script—it tells the story, defines characters, sets up scenes

- The runtime is the program that runs it—like a video player for your Visual Novel

The runtime:

- Reads your JSON file

- Executes each action in order

- Manages game state (where you are in the story, what variables are set)

- Renders graphics and plays audio through Route Graphics

- Handles user input (clicks, choices, menu navigation)

Designing and implementing the runtime happened iteratively together with the JSON structure: they co-evolved. Now that we've described the full JSON object, let's talk about how it's actually implemented in the JavaScript code.

Single State Architecture

This store comprises around 80% of the entire Route Engine codebase.

There is a single big JavaScript object that contains the full state of the Visual Novel runtime. It's called the system store—a single source of truth that's centralized and authoritative. This is very simple and works very reliably.

If you're a frontend developer, this will sound familiar. It's similar to state management libraries, which inspired this design.

The store is comprised of 3 things:

- state

- selectors

- actions

State:

This single state contains all the information needed to build the full Visual Novel and which point in the story the player is at. This state fully explains everything needed to render the current position.

This state has several properties:

projectData: the static JSON object we have been talking about- pointer object that records current sectionId and lineId

- history information about the lines and sections the user has viewed

- variables and their values

- info regarding whether auto mode or skip mode is currently enabled

- and much more

Selectors

Selectors are derived values computed from the raw state. Just straightforward transformations. All selectors are pure functions.

Below are the 2 most complicated selectors, they span multiple hundred lines of code.

presentationState: the final presentation state after computing actions from 1st line of the section to the current line. It tells you which background image, which characters, etc... need to be shown on the screen.renderState: computed frompresentationStateandsystemState. This is sent directly to Route Graphics for updating the screen

Actions

Anything interactive or any change to the state is done through actions. All actions are pure functions.

Some of the common actions are:

nextLine: will move to the next line. usually called during user clickprevLine: go to previous line. used for rollback/history featuresectionTransition: jump to another section. used for branching, scene changes, or menu navigationupdateVariable: modify variable values. used for counters, flags, tracking game statetoggleAutoMode/toggleSkipMode: toggle auto-play or skip modesaveVnData/loadVnData: save or load game stateaddLayeredView/clearLastLayeredView: show or hide layered views like menus, options, or history

Side Effects

A side effect is anything that interacts with the outside world such as rendering to the screen, starting timers, saving data to storage.

Since actions must be pure functions, they can't directly cause side effects. Instead, actions queue side effects to be processed later.

Inside the action, we append effects to the system state's pendingEffects array:

// Stop auto mode - queues timer cleanup and render effects

export const stopAutoMode = ({ state }) => {

state.global.autoMode = false;

state.global.pendingEffects.push({

name: "clearAutoNextTimer",

});

state.global.pendingEffects.push({

name: "render",

});

return state;

};

A separate sideEffectsHandler processes these queued effects. For example, the render effect calls Route Graphics's render function.

This approach keeps actions pure while handling complexity elsewhere. The complicated stuff—timers, async operations, rendering calls—lives in the sideEffectsHandler, keeping the core state management clean and predictable.

This works for asynchronous operations too. When an async operation completes, it triggers another action to update the state.

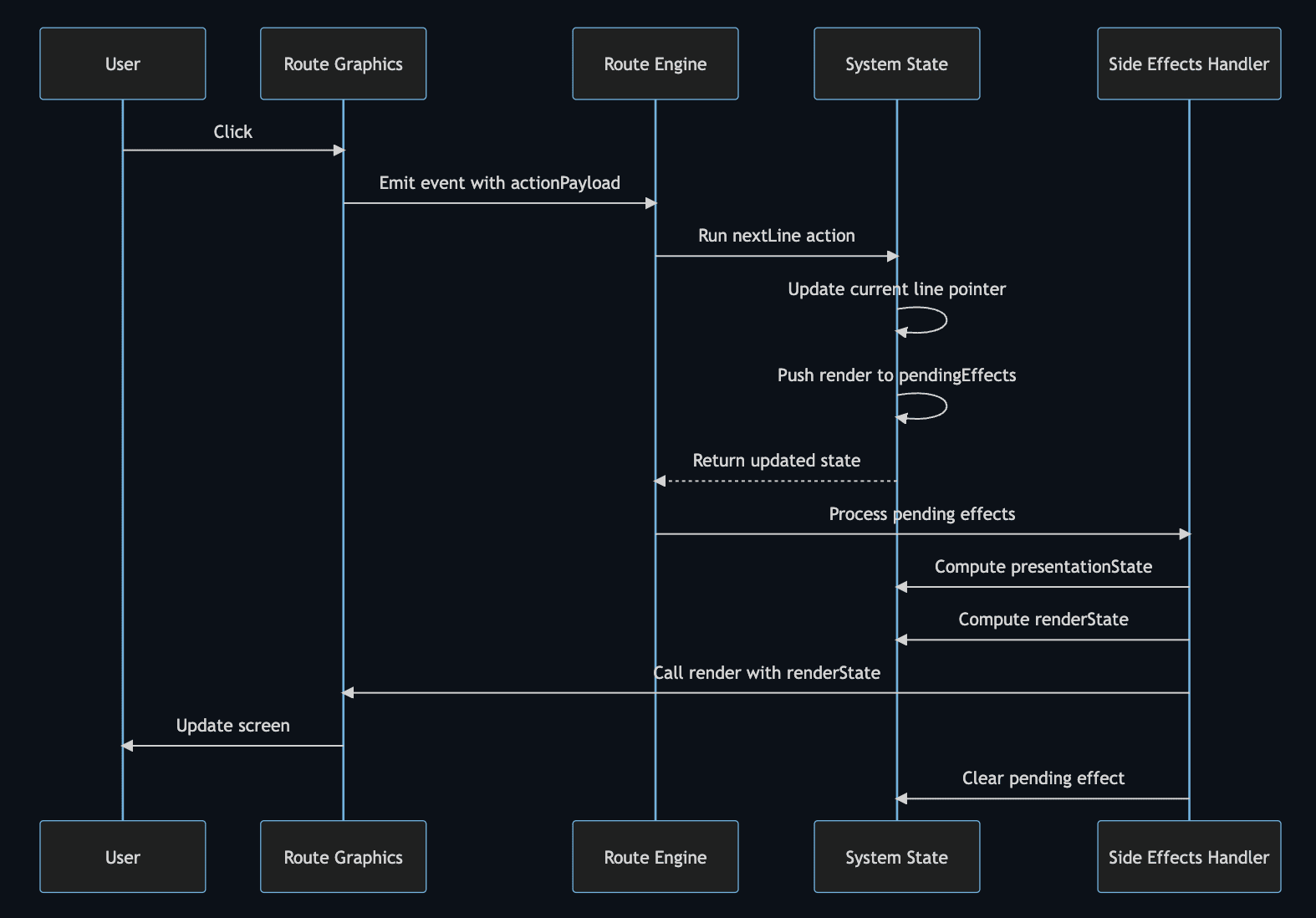

Full Example: Click to Next Line

Below is a full example of how an interaction flows through the entire system:

Flow breakdown:

- User clicks → Route Graphics emits event

- Event handler calls Route Engine to run

nextLineaction - Action calculates and updates the current line in state

- Action pushes

renderside effect topendingEffectsarray - Side Effects Handler processes pending effects

- Selector computes

presentationStatefrom latest state - Selector computes

renderStatefrompresentationState - Route Graphics render is called with

renderState - Screen updates with new content

- Pending effect is removed from queue

Internal Experiments

Internally, we use Route Engine to re-implement some existing short Visual Novels by hand. This tests how much we can do with the engine, what features we support, and what gaps remain.

The current state: it can do a lot of things, but there are still glitches here and there. I'd say we're able to get to around 80% reproduction of existing VNs.

The goal is to reach over 95% reproduction for simple Visual Novels, and then do the same for more advanced ones.

In parallel, we're slowly exposing more of these functionalities to RouteVN Creator so users can benefit from them. This process requires careful handling to ensure features work well across the entire system.

Conclusion

Route Engine is an intentionally designed compact library which has gone through several iterations with the purpose of implementing all features needed in a Visual Novel.

In this article, we've covered:

- The JSON structure: How resources, story hierarchy (scenes, sections, lines, actions), and Jempl templating enable a full Visual Novel to be expressed as a single JSON file

- The runtime architecture: A single state store with pure functions—selectors for derived state, actions for state transitions, and a queued effect system for handling side effects without compromising purity

This design prioritizes maintainability and predictability. By keeping the core as pure functions and pushing complexity to the edges, we can handle advanced features like save/load, rollback, auto/skip modes, and dynamic UI without the codebase becoming unmanageable.

Route Engine is open source under the MIT License.

If you liked this article, consider giving it a star on GitHub.

In the next post, we'll talk about RouteVN Creator, the actual editor, and how it's built on top of Route Engine. We've spent much more time on RouteVN Creator than any other codebase.