Building a Visual Novel Engine Part 3 - RouteVN Creator

This series will explain the whole architecture and design of RouteVN Creator. By the end of the series, you should have a good understanding of how RouteVN Creator works, and essentially how to build a Visual Novel engine from scratch.

This is part 3 of a 3 part series:

- Part 1 - Route Graphics: a declarative graphics and sound library

- Part 2 - Route Engine: a Visual Novel engine built on Route Graphics

- Part 3 - RouteVN Creator: a Desktop application to create Visual Novels without any coding

Product Vision and Design Intent

We saw two common patterns in existing tools for creating Visual Novels.

Script/code-based engines are very powerful, allowing full customizations, but they require technical knowledge and a meaningful learning curve.

UI-based editors offer the other side of the tradeoff:

- Easy at first, but advanced use cases eventually push users back into scripting or technical workflows

- Some of them are more powerful, but with hard to use UI/UX

From the beginning, our product direction had two goals:

-

Make Visual Novel creation more accessible. This means no coding requirement, intuitive UI/UX, and a beginner-friendly flow where creators can start quickly.

-

Build better tools for serious Visual Novels. This means supporting advanced features and richer workflows, while still hiding technical complexity behind clear interfaces. Advanced features include collaboration features for teams.

We took an ambitious approach and tried to aim for both:

- Build first for ease of use

- Then expand to support more powerful features

These two goals create a constant product tension: keep things simple for new users, while still expanding power for advanced use cases.

Below we will explore how we built the application while trying to achieve our design goals.

Technical Foundation

This effort grew into a large engineering project, and we needed a strong foundation to support our vision. That is why we built Route Graphics, Route Engine, and even a frontend framework, Rettangoli.

Most of that technology is invisible to end users, but it is what we work with every day.

RouteVN Creator is the product people actually interact with. It is the user-facing frontend, and it is also the part that took us the most time and care.

Offline and Collaboration Data Structure

Offline applications run without depending on constant server round trips, so user actions can update instantly.

Collaborative applications allow multiple users to work on the same project at the same time and receive updates from each other.

The technologies used to build modern collaborative applications are CRDT and OT (Operational Transformations), and both support collaborative, offline-first workflows.

In principle, the system records actions rather than only the final state, and those actions are synced across users.

We followed this approach, but we did not use standard CRDT/OT implementations directly. We modified the model to fit our needs, especially stronger validation, and built our own library: insieme.

Offline-first behavior simplified many UX flows for us, and in many interactions we did not need loading indicators because data is written locally first.

Building a collaboration library, however, is much more involved because ordering, syncing, and merges must stay correct across clients.

Desktop Application with Tauri

At first we considered building a web-based application, because that is where my experience came from and the web can do almost anything.

Browsers can support offline applications with IndexedDB, but browser data can still be unintentionally lost during cleanup operations.

For us, the biggest limitation of a web app was storage persistence.

Users are also not used to keeping large project data inside the browser.

So we switched to a desktop application, where project data is stored directly on the user's file system. This follows what other game engines do.

To build a cross-platform desktop application with web technologies, we compared Electron and Tauri, and chose Tauri primarily for its lower memory footprint.

It is less mature in some areas, and we had to work around limitations in areas such as installer behavior, updater flow, and file permissions.

Page by Page

Below is the creator workflow page by page, and the most important parts in each one.

Projects and Data Storage

RouteVN Creator is a desktop application that needs to be installed.

We store data at two levels: global and project.

At the global level, we keep one SQLite file for user configuration and the list of projects.

Each project lives in its own folder, with one SQLite file plus the binary assets uploaded by the user. The project SQLite file stores project data, including event logs.

We also use a key-value table so we can extend functionality over time without creating a new schema migration for every small addition.

Resources (Assets and UI)

Resources are split into two groups:

- Assets: images, sounds, videos, characters, and content resources

- UI: colors, fonts, typography, layouts, and interface resources

To keep this large surface area maintainable, we made a few core design decisions:

- We use a consistent page shell across resources: folder navigation, item list, right-side editor panel, and shared create/edit dialogs. This keeps the experience predictable for users and lets us reuse code across many pages.

- We use the same data foundation for all resource types, especially for folder and file organization. The tree model is append-only where possible, which helps reduce conflicts in collaborative workflows.

- We still allow resource-specific customization, because each resource type has different behavior and constraints.

The UI resource pages (colors, fonts, typography) are intentionally structured. They may feel stricter at first, but they scale better as projects grow.

Asset workflows are more straightforward: users upload files, resources are organized by data type rather than use case, and a flexible folder system allows teams to organize content in their own way.

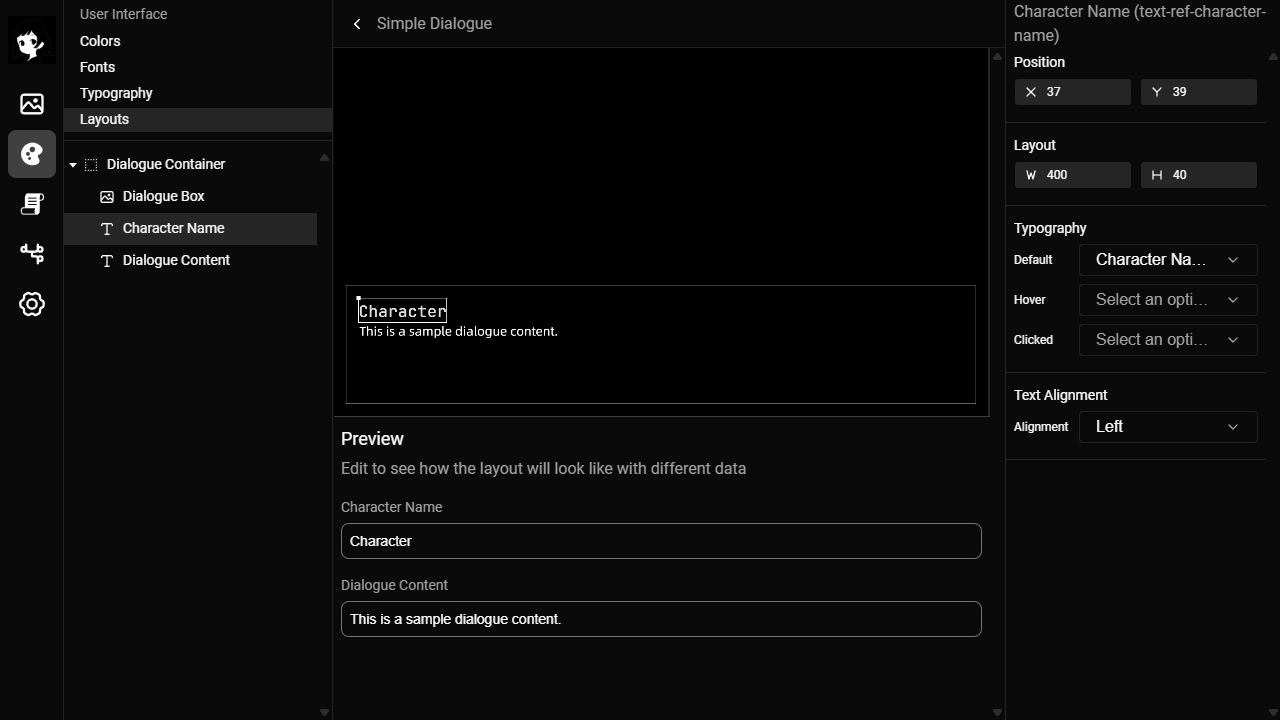

Layout Editor

The Layout Editor was a completely different level of complexity.

We wanted the UI to be fully customizable.

That is not a trivial problem, so we essentially had to build a full-fledged design tool into this page.

Furthermore, it supports advanced behaviors such as hover states, click events, and variables that traditional design tools usually do not provide.

Under the hood, both the layout model and the implementation are complex. Keeping the codebase clean and keeping the UX layout clean are two separate challenges, and we had to solve both.

Scene Map

Scene Map gives a high-level structure of story flow between scenes.

This is where users organize macro story structure before and during detailed writing.

We implemented it with HTML instead of canvas or other more performant approaches. For our use case, this was easier to build and maintain, and performance was not a bottleneck.

Scene Editor

The Scene Editor is where users spend most of their time, so we put a lot of attention and effort into making it good. It is one of the most critical and difficult parts of the whole product.

The live preview is the magical feature: as users write and edit content, the preview updates in real time. The goal is immediate, accurate feedback, so creators can see exactly what they are building without context switching. We were able to do this because we built Route Graphics and Route Engine to support this.

Regarding the text editor itself, at first glance, using an existing rich text editor seems like the obvious choice. We tried that direction, but it did not provide the flexibility we wanted to have.

So we implemented the editor from scratch on top of <div contenteditable>. This is difficult because browser text input has many tricky edge cases. We had to implement a lot of tricky things from scratch:

- A line-based editing model, not just a generic document

- Reliable keyboard flow across lines (split/merge, up/down navigation, left/right edge behavior)

- Stable cursor behavior while the preview updates in real time

- Tight synchronization between selected line and runtime preview state

It took many iterations and a lot of bug fixing around cursor, focus, and line operations. It is still a tricky area, and some features, such as rich text support, are not implemented yet.

Implementing from scratch gave us a lot of control, but we had to handle difficult low-level behavior ourselves, which was very time-consuming.

The upside is that we can keep extending the functionality and improve the editor over time.

Versions and Export

Because our core data model is append-only event logs, versioning comes naturally. Versions are lightweight pointers into that history, so users can go back to any previous state and export the project from that point.

For the export format, we wanted distribution to be as simple as possible. The exported output consists of three files:

index.htmlmain.jspackage.bin

package.bin concatenates all assets and instructions into one payload, with an index that records byte ranges for each item (content-range style lookup).

At runtime, the player resolves content using those ranges, so it can locate exactly what it needs from a single file instead of handling many separate ones.

This keeps distribution simple and portable.

However, due to browser local file permission limitations, the exported project cannot run directly from the local file system and still requires a static file server. We plan to provide a lightweight tool to make local hosting more convenient.

In the future, we also plan to support desktop distribution.

Current State and What is Next

As of this writing, version 0.15.0 is closer to a working prototype than a production product. It proves the idea works, but it needs another significant iteration to become robust and user friendly.

A big part of how we improved RouteVN Creator was running usability tests continuously, usually a few sessions every month.

In earlier tests, many users got blocked by bugs before we could even properly evaluate UX, so a lot of effort went into stability first.

The current product is much better than those earlier versions, but there is still a gap between where we are and our vision of a truly effortless experience.

Our goal in the coming months is to close that gap and push this into a production-ready product. The foundation is there, and the critical paths have been validated. Now we need to refine.